Translated by Ismaeel Nakhuda

The Shaykh, the Imam, the ‘Allamah, the Hadith Scholar Rashid Ahmad ibn Hidaya Ahmad ibn Pir Baksh ibn Ghulam Hasan ibn Ghulam ‘Ali ibn ‘Ali Akbar ibn Qadi Muhammad Aslam al-Ansari al-Hanafi al-Rampuri then al-Gangohi. He was one of the research, learned and accurate ‘ulama. In his age, there was none like him in honesty, virtue, trust in Allah, fiqh, nobility, courage at times of danger, firmness in religion and emphasis in adhering to the (Hanafi) school.

He was born on 6 Dhi ‘l-Qa’da, 1244 AH, in the village of Gangoh at the home of his maternal grandfather. He grew up among his maternal relatives. He was originally from Rampur, a village in the district of Saharanpur.

He studied the books of Persian under his maternal uncle, Muhammad Taqi, and a few short texts in Arabic grammar and etymology under Molwi Muhammad Baksh al-Rampuri. He then travelled to Delhi and studied some Arabic under Qadi Ahmad al-Din al-Jehlami. He then remained in the company of Shaykh Mamluk al-‘Ali Nanautwi and studied most books of the curriculum under him, and some under Mufti Sadr al-Din al-Dehlawi. He studied the majority of books of hadith and exegesis of the Qur’an under Shaykh Abd al-Ghani (al-Dehlawi), and some under his elder brother Ahmad Sa’id ibn Abu Sa’id al-‘Umari al-Dehlawi. He studied until he excelled and superseded his peers in the rational (m’aqul) and transmitted (manqul) sciences.

He then returned to Gangoh and married Khadija, the daughter of his uncle, Muhammad Taqi. He then memorised the Qur’an in a single year and studied tasawwuf under the Great Shaykh Imdad Allah ibn Muhammad Amin al-‘Umari al-Thanawi. He remained with him for some time. He then took up teaching in Gangoh and was accused of participating in the rebellion against the English in the year 1276 AH. So, the authorities arrested him and imprisoned him for six-months in the town of Muzaffarnagar. When his innocence became clear, they released him from captivity. He then, for a short time, occupied himself with teaching and imparting knowledge.

In 1280 AH, he travelled to the Hijaz with the financial support of a man from Rampur. His shaykh, Haji Imdad Allah, who has been mentioned above, had left India before that in 1276 AH. So he met him in Makka and performed his obligatory Hajj. He then travelled to Al-Madina al-Munawwara, where he visited the Prophet’s grave and met his teacher (in hadith) Shaykh ‘Abd al-Ghani. He then returned to India and for some time occupied himself with teaching and imparting knowledge.

He travelled to the Hijaz once more in the year 1294 AH with a group of righteous people, which included Shaykh Muhammad Qasim (al-Nanautwi), Shaykh Muhammad Mazhar (al-Nanautwi), Shaykh Y’aqub (al-Nanautwi), Shaykh Rafi’ al-Din, Shaykh Mahmud al-Hasan al-Deobandi, Mawlana Ahmad Hasan al-Kanpuri and others. He performed the Hajj on behalf of one of his parents and then travelled to Al-Madina al-Munawwara where he remained for twenty days. There he met his teacher, Shaykh ‘Abd al-Ghani. He then returned to Makka, and stayed there for an entire month and benefited from his shaykh, Haji Imdad Allah. After that he returned to India, and to teaching in Gangoh. He then travelled to the Hijaz in 1299 AH and performed the Hajj on behalf of one of his parents. He then travelled to the City of the Prophet (Allah bless him and give him peace), met his teachers and returned to India. He remained in Gangoh and only left once or twice for Deoband to oversee the affairs of the Arabic madrasa there.

Before his journey to the Hijaz on the third occasion, he would teach several sciences, including fiqh, the principles of fiqh, Islamic belief (kalam), hadith and the exegesis of the Qur’an. After his return from the Hijaz on the last occasion, he devoted himself to teaching the six books of authentic (sahih) hadiths, something that he would do in a single year. He would begin with Jami’ al-Tirmidhi and would go to pains in researching the text (matan) and the chain of narration (isnad), dispelling contradictions, giving preference to one of the two sides, and solidifying the Hanafi school (madhhab). He would then lecture the other books – Sunan Abu Dawud, Sahih al-Bukhari, Sahih Muslim, Al-Nasai, Ibn Maja – one after the other with just a little discussion about the actual book. He did not write much.

His time was allotted [stringently. He would adhere to his timetable during the summer and winter. Once he had prayed Fajr, he would occupy himself in solitude with dhikr (remembrance of Allah) and meditation until sunrise. He would then perform nafl (supererogatory) prayers and then turn to his students who comprised eminent ‘ulama and seekers. He would teach them fiqh, hadith and tafsir (exegesis of the Qur’an). Towards the end of his life, he restricted this to the teaching of the six books of authentic hadiths. When he lost his vision, he left teaching and devoted himself to providing spiritual guidance and academic research. After he had left teaching, he occupied himself with writing letters and replies, and answering fatwas (religious edicts). When he was unable to write due to cataracts, he appointed the duties of writing and answering fatwas to his excellent student, Shaykh Muhammad Yahya ibn Isma’il al-Kandehlawi. He would endeavour to complete the tasks as soon as possible. When he (Shaykh al-Gangohi) would finish writing, he would eat lunch, and take a siesta and rest. Once he had offered Zuhr prayers, he would occupy himself with the recitation of the Qur’an whilst looking in. After he had lost his sight, he would recite from memory. He would then occupy himself with teaching until ‘Asr prayers. He would then sit for the general masses between ‘Asr and Maghrib prayers. Once he had performed Maghrib, he would stand and offer supererogatory prayers. He would then return home to his family and take supper. Once he had read ‘Isha prayers, which he generally delayed, he would retire to bed to sleep and rest. This was his habit for years.

He was a brilliant model and a clear blessing in piety (taqwa), the following of the Prophetic way, acting on what is superior, remaining steadfast on the Shari’a, abandoning innovation (bid’a) and newly invented matters and combating them in everyway, keenness in spreading the Sunna, raising the distinguishing features (sh’air) of Islam, coming out openly with the truth and explaining Shari’a rulings. He would not be bothered with what people would say regarding him. He would never accept distortions or tolerate something wrong. Partiality and laxity in matters of religion was unknown to him – this in spite of the disposition of humility, softness and gentleness that Allah had impressed on him. He would adhere to the truth wherever it would be. He would recant a statement when the correct view became clear. Leadership (imama) in knowledge, actions, managing the tarbiyya (spiritual rectification) of murids (disciples), purifying souls, calling to Allah, reviving the Sunna and ending innovation ended with him.

Allah had given him such students and khalifas (spiritual successors) whose existence is rare in this age in terms of steadfastness to the faith, adherence to the noble Shari’a, spreading beneficial knowledge, reviving the Sunna and reforming the Muslims. An innumerable amount of people benefited from them.

The shaykh was of medium height, proportionate sized limbs and medium build. He had a broad forehead, a shiny brow, arched eyebrows and large eyes that would be lowered in shyness. He had a beautiful straight nose and a dense beard. He was broad-shouldered and had a loud voice, which would be gentle and clear. He would always be joyful. He was eloquent, had a beautiful voice, sharp senses and an acute sense of feeling. He was frugal in his life; he was someone who adhered to the middle path between two extremes. He loved cleanliness and elegance. He rejected takalluf (affectation), preferring natural behaviour.

His senior khalifas included Shaykh Khalil Ahmad al-Saharanpuri, Shaykh Mahmud Hasan al-Deobandi, Shaykh ‘Abd al-Rahim al-Raipuri and Shaykh Husayn Ahmad al-Faydabadi (al-Madani). Among his famous students were Shaykh Muhammad Yahya al-Kandehlawi, Shaykh Majid ‘Ali al-Manwi, Shaykh Husayn ‘Ali Alwani and others.

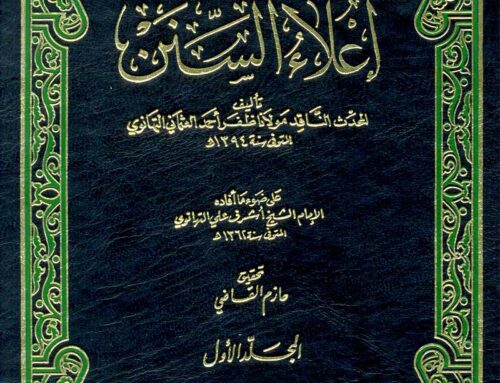

He has a few short books to his name, including Tasfiyat al-Qulub, Imdad al-Suluk, Hidayat al-Shi’a, Zubdat al-Manasik, Hidayat al-M’utadi, Sabil al-Rashad, Al-Barahin al-Qati’a in refutation of Al-Anwar al-Sati’a by Molwi ‘Abd al-Sami’ al-Rampuri, which was published under Shaykh Khalil Ahmad al-Saharanpuri’s name, and a few booklets regarding some disputative fiqh issues and refutations of innovations. Some of his students compiled his booklets for publishing; his fatwas were gathered in three volumes.

His excellent student, Shaykh Muhammad Yahya ibn Isma’il al- Kandehlawi compiled his lectures of Jami’ al-Tirmidhi, which he published under the name Al-Kawkab al-Durri and also compiled his lectures of Sahih al-Bukhari, which were then published by Shaykh Muhammad Zakariyya ibn Shaykh Muhammad Yahya al-Kandehlawi with his footnotes and named Lami’ al-Darari.]

I (‘Allama Sayyid ‘Abd al-Hay ibn Fakhr al-Din al-Hasani), indeed, met him in 1312AH in Gangoh and heard from him the hadiths of Al-Musalsal bi al-Awwaliyya. [1]A famous Prophetic hadith transmitted (with contiguous isnad) with each narrator having heard this particular hadith first before others from the person above them in the chain. He granted me permission (ijaza) to narrate hadith and prayed for blessings for me.

[He died on the day of Friday after the call to prayer (adhan) (of Jumu’a) on the eighth of Jumada al-Ukhra, 1323 AH.]

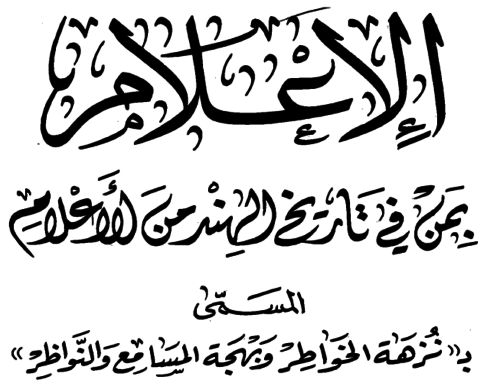

Translator’s note – The biography of Shaykh Rashid Ahmad al-Gangohi is in the eighth volume of ‘Allama Sayyid Abd al-Hay ibn Fakhr al-Din al-Hasani’s magnum opus, Al-I’lam bi man fi Tarikh al-Hind min al-A’lam (also known as a Nuzhat al-Khawatir wa Bahjat al-Masami wa al-Nawadhir), a historical eight-volume record of the biographies of significant individuals from the Indo-Pak subcontinent.

Shaykh Sayyid Abu ‘l-Hasan ‘Ali al-Hasani al-Nadwi, the author’s accomplished son, writes in the preface to the final volume that since his father died before its completion, he carefully undertook the task of finishing the biographies using the same methodology and writing style of his illustrious father.

He adds that the eighth chapter comprised 559 biographies, and that 350 biographies had been left completely or partially blank, or important details had been missed, as the biographer had died before the person whose biography had been recorded. In order to separate his additions and the writings of his father’s, the shaykh used square brackets, which have been preserved in the translation above.

| ↑1 | A famous Prophetic hadith transmitted (with contiguous isnad) with each narrator having heard this particular hadith first before others from the person above them in the chain. |

|---|

As-salamu ‘alaykum,

The respected author’s account of his stay at the Khanqah of Hadrat Mawlana Rashid Ahmad Gangohi (may Allah shower His mercy upon them both) is also worth reading.

Muhammad Habib

I am a South African and took bay’at at the hands of Hazrat Shahidullah Shah Faridi of Karachi, an Englishman who was the successor of Hazrat Muhammad Zauqi who was the successor of Syed Waris Hassan who was successor of Hazrat Rashid Ahmed Gangohi (RA). Masha’allah it is wonderful to read the accounts of these giants of Tassauwuf. Keep up the magnificent work of enlightenment. May Allah bless you.